Renoir: Father and Son/Painting and Cinema. Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia through September 3, 2018; accompanied by an illustrated catalogue published by the Musée d’Orsay and Flammarion in association with the Barnes Foundation.

Ninety-nine years after his death, the reputation of Pierre-Auguste Renoir is endangered. Protestors picketed Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts in 2015 with signs saying his paintings should be removed, and the organizer said that the Renoirs at the Barnes Foundation were “empty calorie-laden steaming piles.” Holland Cotter, art critic at the New York Times, described his work as “cellulite and sunburn.”

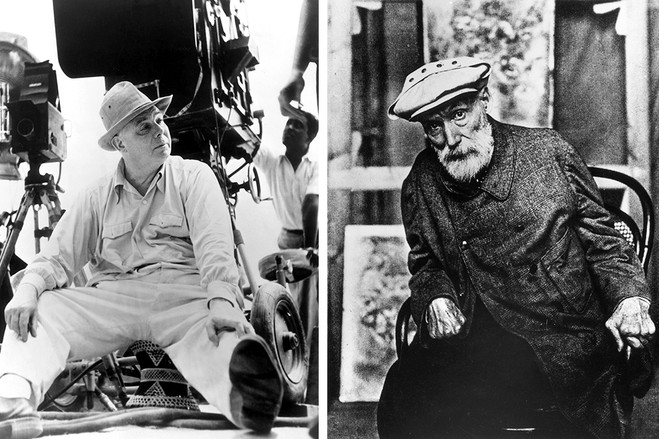

On the other hand, the painter’s son Jean Renoir stands as an august figure (pardon the pun) in the history of film. It’s ironic that Pierre-Auguste Renoir is one of the most famous people of all time, yet his reputation among art professionals has shrunk while Jean enjoys greater prestige within his own circle. This exhibition gives equal billing to father and son but, in effect, it puts the spotlight on Jean, which is a great idea because there are few museums where the public can go to see the work of a film director.

On left, his father’s portrait of young Jean.

On left, his father’s portrait of young Jean.

This is a joint effort of the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia and the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. It presents the artistic connections between the two men, and we’re fascinated by the many references by film-maker Jean to his father’s art. Both father and son focused on intimate relationships of families and friends, and often placed their subjects in rural settings. Both of them produced scenes that appeared to be improvised, even though they were carefully planned. Both drew upon a close-knit circle of family and friends to portray a sense of community.

Jean often filmed intimate stories in the South of France, shooting at bucolic locations and using non-professional actors. This was exactly what his father had done on canvas. Because he suffered from rheumatoid arthritis, the elder Renoir followed his doctor’s recommendation to spend time in the warmer climate of the South and he bought a place there in 1897.

There are relatively few Renoir paintings in the exhibition, but enough to demonstrate the family connections. Of course, within the same building is Albert Barnes’s main collection which includes 181 additional Renoirs. Anyone attending this exhibit must take time to walk through the main galleries. Those rooms also contain many ceramic jars and vases by Jean Renoir, which Barnes collected at a time when the son’s work was virtually unknown. These ceramics have vivid colors and have always been a special treat amongst the paintings in Dr. Barnes’s galleries.

Pierre-Auguste’s paintings of Jean are a delight. In one, the family’s housekeeper Gabrielle tries to entertain one-year-old Jean as he plays with toy animals (pictured here.) In addition to paintings, there’s a lovely lithograph on woven paper of young Jean wearing a bonnet, L’Enfant au Bisquit (Child with a Biscuit.)

Don’t overlook the interesting silver bromide photographic print by Pierre Bonnard of Pierre-August with his son in military uniform, circa 1916 when Jean was 22.

Production photos, posters and film clips of Jean’s movies are flanked by memorabilia such as a reproduction of the dress worn in one film by Jean’s wife Catherine, who had started her career as a model for Jean’s father.

In connection with the exhibition, Lightbox Film Center at International House Philadelphia is presenting six films of Jean Renoir on Friday nights throughout the summer. Jean’s film Toni (1935) was shot on location and used non-professional actors. A long take of one woman rowing away from land and towards a limitless future is spellbinding. A Day In The Country (1936) shows a group of Parisians spending a serene Sunday afternoon, and its final shot of a woman on a swing links us to his father’s famous painting The Swing (1887) which also is part of this exhibit.

La Bête Humaine (The Human Beast, 1938) is a dark movie with a story about murder from Emil Zola’s novel, starring Simone Simon and Jean Gabin. The Rules of the Game (1939) is a playful dissection of upper-class life.

Renoir directed five Hollywood films in the 1940s, and clips illustrate Jean’s commercial progress. Ultimately comes Renoir‘s 1951 Technicolor masterpiece The River. The film’s narrator recalls memories of her childhood in India when “time passed, unnoticed.” French Cancan (1955) and Elena and Her Men (1956, with Ingrid Bergman) are well documented.

I’m fascinated by scenes from Jean’s films that reveal Pierre-Auguste’s paintings in the background, and several photographs of Jean in his Beverly Hills home with his father’s paintings hanging on the walls — plus a similar photograph in Jean’s Paris apartment in 1955 where actress Leslie Caron happens to be visiting.

Don’t miss the motion picture of Pierre-Auguste at work in his studio in 1919, the year of his death, with the old man’s arthritic hands wrapped in bandages.

Renoir: Father and Son/Painting and Cinema, is a book/catalogue published by the Musée d’Orsay and Flammarion in association with the Barnes Foundation.

See these other reports about Barnes exhibitions of photography here; and Picasso here; and Rodin here.

Below, Jean and his pottery displayed at the Barnes Foundation: